Last night I went to see the play at Finsbury Park Theatre about that other Lee: Lee Krasner, the painter-wife of Jackson Pollock. The central theme was how Krasner, a talented artist, was sidelined by Pollock during his lifetime. No one could take seriously that a woman might be an accomplished Abstract Expressionist. Abstract Expressionism was for men. The American photographer, Lee Miller, similarly had to break through a glass ceiling in a predominantly man’s world, continually reinventing herself from fashion model – photographed by the likes of Edward Steichen and Cecil Beaton – to became one of the very few accredited female war photographers of the Second World War, and among the first to document the horrors of Dachau, which she brought back to a disbelieving world on the unlikely pages of British and American Vogue.

Born in 1907 in Poughkeepsie, New York, where her father was a keen amateur photographer, Lee initially studied painting and stage design. However, with her natural flair and androgynous good looks that exemplified the beauty ideals of the time, she soon found herself modelling. A strip of four photographs at the beginning of the Tate exhibition, snapped in one of New York’s first automated photo booths, shows a gamine girl in a cloche hat. The same cloche hat she wore for her debut on the cover of Vogue in March 1927. Legend has it that Condé Montrose Nast discovered her as a 19-year-old on a New York sidewalk, where he was immediately captivated by her boyish beauty. Her developing interest in photography led her to move from being a model and muse in front of the camera to becoming a powerful, independent creative force behind the lens.

Lee Miller had an instinct for finding the pulse of things. A move to Paris in 1929 saw her become assistant, collaborator and sometime lover to Man Ray. Presenting herself at his studio unannounced, she declared she was his new student. He answered that he didn’t take students, and anyway, he was about to go on holiday. Okay, she said, she would go with him. Man Ray had a profound effect on how she saw the world, leading to her uncanny landscapes and sideways looks at both people and things. Although never formally aligned with any art movement, she was always open to new techniques, fearless and determined. ‘It was a matter, ’ she said, ‘of getting out on a damn limb and sawing it off behind you.’

This triumphant exhibition loosely charts her development through five decades, navigating her involvement in the glittering avant-garde circles of pre-war Paris, through to her gritty wartime photorealism. What comes across is the development of a brilliant, sassy, vulnerable and indomitable woman who wouldn’t take no for an answer.

The outbreak of the Second World War found her living in London after two years in Cairo with her then-wealthy Egyptian husband, whom she left, along with the increasing boredom she experienced there, for the critic, collector, and British Surrealist Roland Penrose. The images from Egypt, torn screens and shrouded statues, are framed and cropped to give everyday objects an unexpected, surreal feel. Many are shown here for the first time. A summer spent in Cornwall with Penrose led to a ‘sudden Surrealist invasion’ when they were joined by Man Ray, Paul Eluard and his wife Nusch. Lee seemed to have a gift for knowing anybody who was anybody, including Charlie Chaplin, Leonora Carrington and Eileen Agar.

A move to London in 1939 at the outbreak of war saw her become the premier fashion photographer for British Vogue, having previously run her own studio in New York. Her striking, observant photographs of the Blitz-torn city include a bomb damaged Dolphin Square and a non-conformist chapel where the rubble from a recent hit appears to be vomited out of the doorway’s classical dimensions.

She went on not only to document women’s lives on the home front, but also to capture the deprivation and devastation in post-war communities across Europe. French women accused of collaboration, shamed by having their heads publicly shaved, and the evacuation of hospitals in Normandy. One hideously wounded young soldier, bandaged from head to toe, like the Invisible Man, asked her to take his photograph so he could see ‘how funny he looked.’ She never flinched. Never turned away. Perhaps her most famous photograph is that taken with David E. Scherman. She is sitting naked in Hitler’s bath. It is shown here, in ironic juxtaposition to the revealed horrors of the Dachau concentration camp. It was gruelling and emotionally demanding work. She wrote to Penrose of her encounters with Germans, ‘I’m becoming hard and hateful.’ In American Vogue, a magazine more accustomed to models on catwalks than gritty photorealism, she published two pairs of startling photographs under the titles:‘ German children, well-fed, healthy….burned bones of starved prisoners,’ and ‘Orderly villages, patterned quiet ….orderly furnaces to burn bodies.’

Entering Buchenwald concentration camp, just days after it was liberated, she was to discover that it had not been run by Übermensch but by ordinary men turned into sadists and monsters. A beaten SS guard shows on a peasant-like face, bloodied and filthy after a beating. You can feel her revulsion alongside the compassion. Among the most searing images are those of a group of prisoners standing broken and blank by a pile of charred human remains. They stare straight into her lens, all life sucked out of them. These would be published in American Vogue in June 1945 under the title ‘Believe It’. What she saw would haunt her for the rest of her life. History and the world owe her a debt for never flinching, for establishing the unvarnished truth.

In 1947, she married Roland Penrose. After the war, she remained extremely private about her war work, which was hidden away in the attic of the Sussex farmhouse, Farleys, only to be discovered after her death. Throughout the 1950s, she continued to write for Vogue and photograph guests, including Picasso, Man Ray, and Max Ernst, who frequently visited. Farleys gave her a chance to heal and distract herself with new projects. Cookery became an escape. She took an advanced Cordon Bleu course and lost herself in producing ever-more surreal meals such as ‘cauliflower breasts’ doused in pink mayonnaise. But the war and what she had seen stayed with her. She had PTSD and became dependent on alcohol; all the while trying to work, renovate the crumbling farmhouse and look after young children.

Her son, Anthony Penrose, is brutally honest about his relationship with his mother. ‘We hated each other when I was a teenager.’ At the time, no one was really aware of the trauma that she underwent, witnessing the horrors of the camps. It was only after she was dead and he was doing research for the film Lee, starring Kate Winslet, that he began to feel emotionally connected to his ‘difficult’ and often drunk mother, to understand her. Possibly, she never really healed. This once beautiful socialite had seen too much, witnessed too many unspeakable horrors, and became a primary witness to the 20th century’s most brutal events. It is thanks to her indomitable courage, to the legacy she left, that those who would deny the horrors of war, particularly the holocaust, will constantly be confronted with the unvarnished reality she fearlessly brought back.

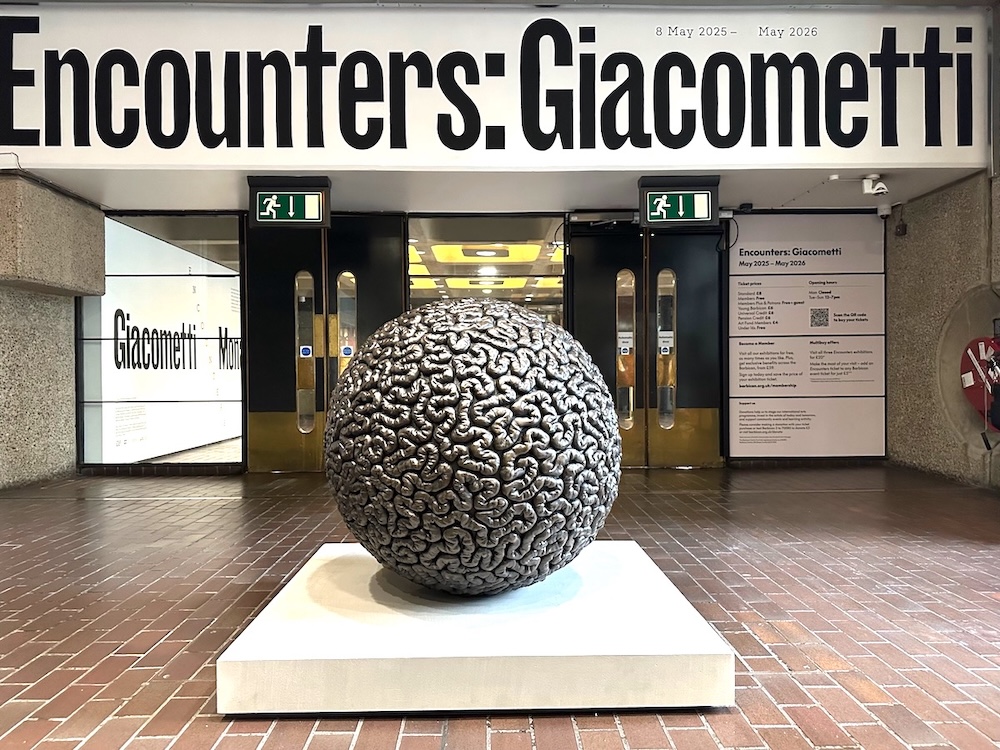

Lee Miller, Tate Britain, 2 October 2025 – 15 February 2026

When she first took to the streets her photographic landscapes, which included Time Square, Coney Island and the street fairs of Little Italy, were similar to those of her predecessors and contemporaries such as Paul Strand and Lee Friedlander. But her photographs, snatched through doorways and shop windows, display a dispassionate voyeurism, rendering her something of an urban anthropologist who objectively observed the strange customs and happenings that she stumbled upon. Through her eyes, the mundane became edgy, whether she was photographing an ample naked woman in a white bathing hat showering on the beach at Coney Island or, what looks like, one of Sweeny Todd’s potential victims through an ordinary barbershop window in 1957 New York. It’s as though she was on a permanent lookout for the odd and the transgressive. As she wrote to a friend in 1960, “I don’t press the shutter. The image does. And it’s like being gently clobbered.”

When she first took to the streets her photographic landscapes, which included Time Square, Coney Island and the street fairs of Little Italy, were similar to those of her predecessors and contemporaries such as Paul Strand and Lee Friedlander. But her photographs, snatched through doorways and shop windows, display a dispassionate voyeurism, rendering her something of an urban anthropologist who objectively observed the strange customs and happenings that she stumbled upon. Through her eyes, the mundane became edgy, whether she was photographing an ample naked woman in a white bathing hat showering on the beach at Coney Island or, what looks like, one of Sweeny Todd’s potential victims through an ordinary barbershop window in 1957 New York. It’s as though she was on a permanent lookout for the odd and the transgressive. As she wrote to a friend in 1960, “I don’t press the shutter. The image does. And it’s like being gently clobbered.” Her early chance encounters, which resulted in photographs such as Woman in a mink stole and bow shoes, N.Y.C 1960, and the image of a hirsute man in pork pie hat, boxer shorts and black shoes and socks standing on the beach in Coney Island, gave way to photographs such as Jack Dracula at a bar, New London Conn, 1961 in which the heavily tattooed young man sits in front of his glass of beer staring confidently at the viewer. From the ghoulish curiosity shown in a pair of Siamese twins preserved in a glass jar in a New Jersey carnival tent, Arbus’s role as a curious observer changed to one of privileged insider. She claimed: “I have learned to get past the door from the outside to the inside. One milieu leads to another.” There’s the sense that in The Human Pincushion, Ronald C. Harrion N.J. 1961 – where a middle-aged white man stands pierced with hatpins like some downtown secular Saint Sebastian – or the moustachioed Mexican dwarf striped to the waist beneath his little trilby in his N.Y.C hotel, are complicit in the making of the image. That Arbus’s half of the bargain was to make them visible and feel singled out from the crowd. There’s a strong sense running through all these images – particularly those of the many ‘female impersonators’ – that self-worth comes from being seen and recorded – even if harshly. But it often feels, despite her unerring eye, as though there is not much compassion in these photos. As she said: Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot…There’s a quality of legend about freaks….. You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw’.

Her early chance encounters, which resulted in photographs such as Woman in a mink stole and bow shoes, N.Y.C 1960, and the image of a hirsute man in pork pie hat, boxer shorts and black shoes and socks standing on the beach in Coney Island, gave way to photographs such as Jack Dracula at a bar, New London Conn, 1961 in which the heavily tattooed young man sits in front of his glass of beer staring confidently at the viewer. From the ghoulish curiosity shown in a pair of Siamese twins preserved in a glass jar in a New Jersey carnival tent, Arbus’s role as a curious observer changed to one of privileged insider. She claimed: “I have learned to get past the door from the outside to the inside. One milieu leads to another.” There’s the sense that in The Human Pincushion, Ronald C. Harrion N.J. 1961 – where a middle-aged white man stands pierced with hatpins like some downtown secular Saint Sebastian – or the moustachioed Mexican dwarf striped to the waist beneath his little trilby in his N.Y.C hotel, are complicit in the making of the image. That Arbus’s half of the bargain was to make them visible and feel singled out from the crowd. There’s a strong sense running through all these images – particularly those of the many ‘female impersonators’ – that self-worth comes from being seen and recorded – even if harshly. But it often feels, despite her unerring eye, as though there is not much compassion in these photos. As she said: Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot…There’s a quality of legend about freaks….. You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw’.

This wonderful exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, held to mark the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death, is part of a yearlong celebration. For the first time, they are showing all 22 paintings, 60 drawings and more than 300 of the finest examples of the Rembrandt’s prints in their collection. It explores different aspects of Rembrandt’s life and works through a variety of themes. The first section is predominantly made up of self-portraits. The second focuses on his surroundings and the people in his life: his mother, his wife Saskia as she lies ill and pregnant in bed, as well as beggars, buskers and vagrants that illustrate Rembrandt had an ability to depict poses and emotional states with great empathy. The last section demonstrates his gifts as a storyteller. Old Testament tales inspired paintings such as the exquisite Isaac and Rebecca, more commonly known as The Jewish Bridge c 1665-1669, a work of such consummate skill in its handling of paint and one imbued with such deep tenderness that it takes the breath away, even after countless viewings.

This wonderful exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, held to mark the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death, is part of a yearlong celebration. For the first time, they are showing all 22 paintings, 60 drawings and more than 300 of the finest examples of the Rembrandt’s prints in their collection. It explores different aspects of Rembrandt’s life and works through a variety of themes. The first section is predominantly made up of self-portraits. The second focuses on his surroundings and the people in his life: his mother, his wife Saskia as she lies ill and pregnant in bed, as well as beggars, buskers and vagrants that illustrate Rembrandt had an ability to depict poses and emotional states with great empathy. The last section demonstrates his gifts as a storyteller. Old Testament tales inspired paintings such as the exquisite Isaac and Rebecca, more commonly known as The Jewish Bridge c 1665-1669, a work of such consummate skill in its handling of paint and one imbued with such deep tenderness that it takes the breath away, even after countless viewings. Above all Rembrandt was interested in people. Not stereotypes or ideas but real living flesh and blood characters. Salacious depictions were hardly unknown in the 17th century, but his etchings of a man and a woman pissing go beyond mere voyeurism into a form of social realism. His wife Saskia is shown in numerous poses. His fluid lines suggest that often he drew directly onto the copper etching plates. He’d cover the plate with a mixture of resin and beeswax, then draw through that surface with a needle to expose the metal. The plate would then be immersed in acid, inked and put through a printing press. One of the most touching is a small etching of his young son, Titus as a 15-year-old, executed in a bare minimum of lines. Titus’s shock of hair and pensive gaze are particularly compelling. Etchings rarely came into being in a single session. In the early years, when still gaining experience, he might begin with the head, move onto the torso and finally add the background. A master of light and dark, he used contrasts to add emotional depth and range.

Above all Rembrandt was interested in people. Not stereotypes or ideas but real living flesh and blood characters. Salacious depictions were hardly unknown in the 17th century, but his etchings of a man and a woman pissing go beyond mere voyeurism into a form of social realism. His wife Saskia is shown in numerous poses. His fluid lines suggest that often he drew directly onto the copper etching plates. He’d cover the plate with a mixture of resin and beeswax, then draw through that surface with a needle to expose the metal. The plate would then be immersed in acid, inked and put through a printing press. One of the most touching is a small etching of his young son, Titus as a 15-year-old, executed in a bare minimum of lines. Titus’s shock of hair and pensive gaze are particularly compelling. Etchings rarely came into being in a single session. In the early years, when still gaining experience, he might begin with the head, move onto the torso and finally add the background. A master of light and dark, he used contrasts to add emotional depth and range.

And what does he want the Summer Exhibition to look like? After all Michael Craig-Martin painted the walls pink. “Well I’m going to have a menagerie. There’s a tradition of animal painting from Stubbs to the more amateur cat paintings traditionally submitted to the RA summer show. Our interest in depicting animals goes back to our first image-making in caves. But the truth is that you don’t know what is going to be submitted and it’s a committee decision. This year’s committee is made up of: Stephen Chambers, Anne Desmet, Hughie O’Donoghue, Spencer de Grey, Timothy Hyman, Barbra Rae, Bob and Roberta Smith, the Wilson twins and Richard Wilson, so it’s quite a cross section.”

And what does he want the Summer Exhibition to look like? After all Michael Craig-Martin painted the walls pink. “Well I’m going to have a menagerie. There’s a tradition of animal painting from Stubbs to the more amateur cat paintings traditionally submitted to the RA summer show. Our interest in depicting animals goes back to our first image-making in caves. But the truth is that you don’t know what is going to be submitted and it’s a committee decision. This year’s committee is made up of: Stephen Chambers, Anne Desmet, Hughie O’Donoghue, Spencer de Grey, Timothy Hyman, Barbra Rae, Bob and Roberta Smith, the Wilson twins and Richard Wilson, so it’s quite a cross section.”

There are also ‘portraits’ of Cy Twombly, Mario Merz, Claes Oldenburg, Merce Cunningham and the poet and translator, Michael Hamburger. Stillness and quietness run through these works. In the film about Hamburger, he barely appears at all. We mostly see his gnarled hands turning his collection of apples from his apple orchard in fractured English autumn light, as a poet might turn over single words. You can almost smell the withered musty skins.

There are also ‘portraits’ of Cy Twombly, Mario Merz, Claes Oldenburg, Merce Cunningham and the poet and translator, Michael Hamburger. Stillness and quietness run through these works. In the film about Hamburger, he barely appears at all. We mostly see his gnarled hands turning his collection of apples from his apple orchard in fractured English autumn light, as a poet might turn over single words. You can almost smell the withered musty skins. She has said that she is interested in objects in the landscape and has included some wonderful paintings of 1814 by Thomas Robert Guest of Bronze Age and Saxon Grave Goods, excavated from a Bell Barrow in Wiltshire.. Her own passion for the painter Paul Nash is underlined by the inclusion of his Event on the Downs of 1934, with its gnarled tree stump and mysterious tennis ball, which has been set between her diptych Ideas for a Sculpture in a Setting, inspired by one of the many flints collected by Henry Moore and kept in his studio. Shot is black and white the object becomes part vertebrae, part talisman, echoing the rock formations and stone henges to be found in this part of the countryside.

She has said that she is interested in objects in the landscape and has included some wonderful paintings of 1814 by Thomas Robert Guest of Bronze Age and Saxon Grave Goods, excavated from a Bell Barrow in Wiltshire.. Her own passion for the painter Paul Nash is underlined by the inclusion of his Event on the Downs of 1934, with its gnarled tree stump and mysterious tennis ball, which has been set between her diptych Ideas for a Sculpture in a Setting, inspired by one of the many flints collected by Henry Moore and kept in his studio. Shot is black and white the object becomes part vertebrae, part talisman, echoing the rock formations and stone henges to be found in this part of the countryside. And does the work really justify all this space in three public institutions simultaneously? Well, yes and no. Dean is an interesting artist. At her best quietly poetic, as in the painterly The Green Ray, 2001 where we can glimpse, if we are patient, the brief refractive green flash caused by the sun setting over the sea. Here she captures something atavistic, in real time, something sublime that could not be caught on anything other than film. Though her use of light she touches on the history of painting, on the primal and creates a sort of truth.

And does the work really justify all this space in three public institutions simultaneously? Well, yes and no. Dean is an interesting artist. At her best quietly poetic, as in the painterly The Green Ray, 2001 where we can glimpse, if we are patient, the brief refractive green flash caused by the sun setting over the sea. Here she captures something atavistic, in real time, something sublime that could not be caught on anything other than film. Though her use of light she touches on the history of painting, on the primal and creates a sort of truth.

In Vase of Flowers, 1924, which includes as its centrepiece the green Andalusian glass vase purchased in Granada in the winter of 1910-11, also included in this exhibition, we find a number of Matisse’s favourite motifs: the open window, the sea and sky, a vase of flowers, patterned wallpaper, a striped cloth, and a net curtain flapping like a translucent veil emphasising the boundary between inside and out. The vase not only functions as a ‘souvenir’ of his travels but underpins memories of the Islamic interiors that had so impressed him on his visit to the Alhambra on the same trip. This sublime painting, full of Mediterranean warmth, air, and light, captures the prelapsarian mood created within his studio with its tapestries and paintings, flowers and furniture, such as his favourite Venetian chair that he painted on numerous occasions. But his studio was not only a sort of lost Eden but ‘a working library’ of objects that had an almost anthropomorphic relationship one with the other. “To copy the objects in a still-life is nothing; one must render the emotion they awaken…” he said. The object became an ‘actor’, so that his much-loved silver chocolate pot is alive to its neighbouring objects whose reflections are caught shimmering in its rotund belly. Based on dialogue and connection these objects cannot be seen in isolation but reflect an almost human sympathy one with another. The ‘reality’ is no longer a purely visual one, arrived at by copying. The object has become an emotional vector. As for Freud, Matisse’s objects reflect an inner mental and emotional reality.

In Vase of Flowers, 1924, which includes as its centrepiece the green Andalusian glass vase purchased in Granada in the winter of 1910-11, also included in this exhibition, we find a number of Matisse’s favourite motifs: the open window, the sea and sky, a vase of flowers, patterned wallpaper, a striped cloth, and a net curtain flapping like a translucent veil emphasising the boundary between inside and out. The vase not only functions as a ‘souvenir’ of his travels but underpins memories of the Islamic interiors that had so impressed him on his visit to the Alhambra on the same trip. This sublime painting, full of Mediterranean warmth, air, and light, captures the prelapsarian mood created within his studio with its tapestries and paintings, flowers and furniture, such as his favourite Venetian chair that he painted on numerous occasions. But his studio was not only a sort of lost Eden but ‘a working library’ of objects that had an almost anthropomorphic relationship one with the other. “To copy the objects in a still-life is nothing; one must render the emotion they awaken…” he said. The object became an ‘actor’, so that his much-loved silver chocolate pot is alive to its neighbouring objects whose reflections are caught shimmering in its rotund belly. Based on dialogue and connection these objects cannot be seen in isolation but reflect an almost human sympathy one with another. The ‘reality’ is no longer a purely visual one, arrived at by copying. The object has become an emotional vector. As for Freud, Matisse’s objects reflect an inner mental and emotional reality. During the mid-1930s Matisse’s art underwent a radical transformation, in which drawing played a crucial role. Here the energy seems to flow so that people and things appear to float within abstract space, rendering everything of equal weight and value. This dynamic freedom was further explored within the suggested rectangular grid cut-outs such as Panel with Mask, 1947. As he said in 1951 the cut-out became, “the simplest and most direct way to express myself.” With these flat, bright forms he created a series of signs, dependent not on the recognition of an object but on the emotional charge created through shape and colour.

During the mid-1930s Matisse’s art underwent a radical transformation, in which drawing played a crucial role. Here the energy seems to flow so that people and things appear to float within abstract space, rendering everything of equal weight and value. This dynamic freedom was further explored within the suggested rectangular grid cut-outs such as Panel with Mask, 1947. As he said in 1951 the cut-out became, “the simplest and most direct way to express myself.” With these flat, bright forms he created a series of signs, dependent not on the recognition of an object but on the emotional charge created through shape and colour.

In another painting from the same decade, In a Hotel Garden (1974) we can virtually feel the fierce midday sun pulsing beyond the suggested window frame, the patches of cool air circulating beneath the abstracted blue and white stripped awning, the filtered shadows penetrating the arched leaves of the palm tree. But Hodgkin isn’t a realistic painter. He doesn’t describe. He immerses himself in a particular time and place to recapture it later in the studio, like Wordsworth recollecting his emotions in tranquillity. In 1967, after several days spent in Delhi with the British Council representative and his wife, he painted Mrs. Acton Delhi (1967-71), possibly his most figurative painting. The odalisque-style figure of Mrs Acton, made up of spheres and curves, reclines languidly on the left hand side of picture space. It was during this period that Hodgkin decided to move from painting on canvas to wood, saying, “I want to be able to attack again and again and again, and the trouble with canvas is that if you attack it more than once or twice, there’s nothing left.”

In another painting from the same decade, In a Hotel Garden (1974) we can virtually feel the fierce midday sun pulsing beyond the suggested window frame, the patches of cool air circulating beneath the abstracted blue and white stripped awning, the filtered shadows penetrating the arched leaves of the palm tree. But Hodgkin isn’t a realistic painter. He doesn’t describe. He immerses himself in a particular time and place to recapture it later in the studio, like Wordsworth recollecting his emotions in tranquillity. In 1967, after several days spent in Delhi with the British Council representative and his wife, he painted Mrs. Acton Delhi (1967-71), possibly his most figurative painting. The odalisque-style figure of Mrs Acton, made up of spheres and curves, reclines languidly on the left hand side of picture space. It was during this period that Hodgkin decided to move from painting on canvas to wood, saying, “I want to be able to attack again and again and again, and the trouble with canvas is that if you attack it more than once or twice, there’s nothing left.”

Staged by the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the aim of the original 19th exhibition was to promote technological innovation. This was met by riots from Chartist protestors in Birmingham’s Bullring. Frightened, angry and discombobulated by the rise in these new-fangled technologies, the Luddite riots reflected the uneasy economic split that was beginning to occur between old crafts and new industry. As I looked out of the ‘window’ of the virtual room into the virtual streets, policemen in white trousers were marching back and forth as Chartists with swords, pikes and flaming torches gathered and shouted, throwing eggs at the window. It was hard, during this immersion, to escape the parallels with today’s politics, where increasing unemployment is being generated by new technologies that render numerous jobs obsolescent. That many, today, blame ‘experts’ and the ‘intellectual elite’, seems little different to the emotions motivating the crowd hurling insults at Fox Talbot and his scientific friends ensconced in King Edward’s School.

Staged by the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the aim of the original 19th exhibition was to promote technological innovation. This was met by riots from Chartist protestors in Birmingham’s Bullring. Frightened, angry and discombobulated by the rise in these new-fangled technologies, the Luddite riots reflected the uneasy economic split that was beginning to occur between old crafts and new industry. As I looked out of the ‘window’ of the virtual room into the virtual streets, policemen in white trousers were marching back and forth as Chartists with swords, pikes and flaming torches gathered and shouted, throwing eggs at the window. It was hard, during this immersion, to escape the parallels with today’s politics, where increasing unemployment is being generated by new technologies that render numerous jobs obsolescent. That many, today, blame ‘experts’ and the ‘intellectual elite’, seems little different to the emotions motivating the crowd hurling insults at Fox Talbot and his scientific friends ensconced in King Edward’s School.